Unlocking the Mysteries of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Managing CAH

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, often abbreviated as CAH, is a fascinating yet complex genetic disorder that affects thousands of people worldwide, influencing everything from hormone production to physical development. As awareness grows, more families and individuals are seeking reliable information to navigate this condition effectively. This in-depth exploration delves into the intricacies of CAH, drawing from trusted medical sources to provide accurate, helpful insights. Whether you're a parent concerned about newborn screening results, an adult managing symptoms, or simply curious about endocrine health, this guide aims to empower you with knowledge. By understanding CAH's causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options, you can better appreciate the advances in medical care that allow those affected to lead fulfilling lives.

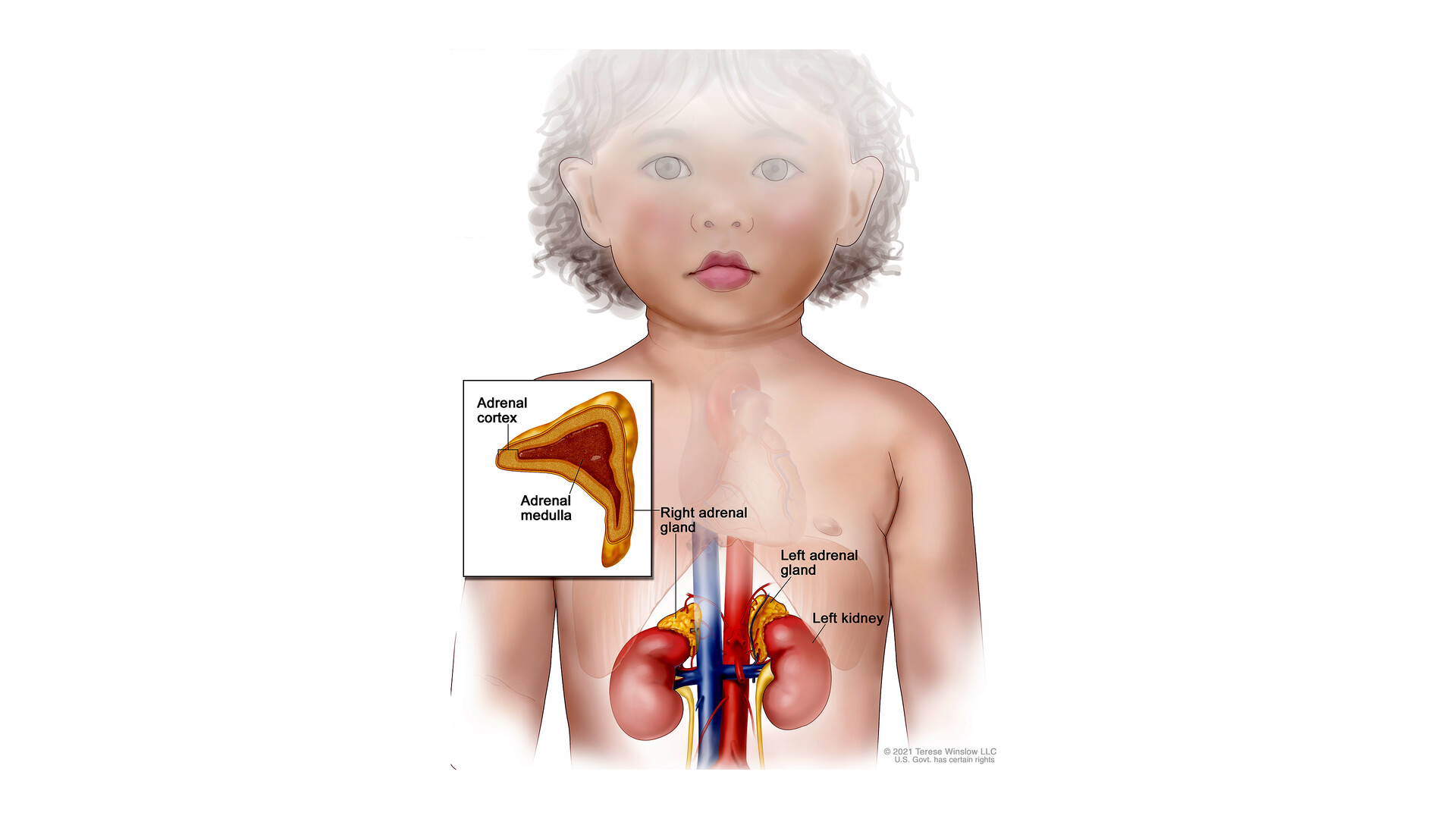

What is Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia?

At its core, Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia is a group of inherited genetic disorders that disrupt the normal function of the adrenal glands, those small but mighty organs perched atop the kidneys. These glands are responsible for producing vital hormones like cortisol, which helps the body respond to stress and regulate metabolism; aldosterone, which maintains electrolyte balance; and androgens, which play a role in development and reproduction. In CAH, a genetic mutation leads to a deficiency in one of the enzymes required for hormone synthesis, most commonly 21-hydroxylase, accounting for about 95 percent of cases. This enzyme shortfall causes the adrenal glands to overproduce certain hormones while underproducing others, leading to a cascade of effects on the body. The condition is autosomal recessive, meaning a child must inherit faulty genes from both parents, who are often asymptomatic carriers. This inheritance pattern explains why CAH can appear unexpectedly in families without prior history.

The disorder manifests in two primary forms: classic and nonclassic. Classic CAH is the more severe variant, typically detected at birth or in early infancy, and it can be further divided into salt-wasting and simple virilizing subtypes. The salt-wasting form, which affects about 75 percent of classic cases, involves deficiencies in both cortisol and aldosterone, posing immediate risks like dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Simple virilizing CAH, on the other hand, primarily involves cortisol deficiency and excess androgens without the severe salt loss. Nonclassic CAH is milder and often goes undiagnosed until later in life, sometimes not until adolescence or adulthood, when subtle symptoms emerge. Rare forms of CAH stem from deficiencies in other enzymes, such as 11-beta-hydroxylase or 17-alpha-hydroxylase, each presenting unique hormonal imbalances that can lead to hypertension or undervirilization. Globally, classic CAH affects approximately 1 in 10,000 to 15,000 newborns, while nonclassic CAH is more common, impacting 1 in 100 to 200 people, with higher prevalence in certain ethnic groups like Ashkenazi Jews or those of Mediterranean descent.

The Genetic and Pathophysiological Roots of CAH

Diving deeper into the science, CAH arises from mutations in genes that encode enzymes crucial for steroidogenesis, the process by which cholesterol is converted into steroid hormones in the adrenal cortex. The most prevalent mutation affects the CYP21A2 gene on chromosome 6, leading to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. This disruption halts the normal production of cortisol and aldosterone, prompting the pituitary gland to release more adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in a feedback loop. The excess ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to enlarge—hence the term "hyperplasia"—and diverts precursors toward androgen production, resulting in elevated testosterone-like hormones. In classic salt-wasting CAH, the lack of aldosterone causes sodium excretion and potassium retention, which can trigger life-threatening adrenal crises, especially in newborns under stress from illness or infection.

For rarer enzyme deficiencies, the pathophysiology varies. For instance, 11-beta-hydroxylase deficiency leads to an accumulation of deoxycorticosterone, a mineralocorticoid precursor that causes high blood pressure and low potassium levels. Similarly, 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency impairs multiple hormone pathways, affecting both glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, and can result in ambiguous genitalia in both sexes. These genetic variations create a spectrum of severity, from asymptomatic carriers to individuals requiring lifelong medical intervention. Understanding this genetic basis is key, as it underscores the importance of family history and genetic counseling for those planning pregnancies, particularly if there's a known risk.

Recognizing the Symptoms Across Life Stages

Symptoms of CAH can be as varied as the enzyme deficiencies themselves, often differing by sex, age, and type. In classic CAH, female infants may present with ambiguous genitalia at birth, where excess androgens cause the clitoris to enlarge and resemble a penis, or the labia to fuse, mimicking a scrotum. Internal reproductive organs like the uterus and ovaries typically develop normally, but external appearances can lead to initial gender assignment challenges. Male infants with classic CAH often appear normal at birth but may later show signs of precocious puberty, such as early pubic hair growth, rapid height increases, and advanced bone maturation, which paradoxically can result in shorter adult stature if untreated.

Both sexes in classic CAH face the risk of adrenal crisis, a medical emergency characterized by vomiting, dehydration, low blood sugar, confusion, and shock, often triggered by stress or illness. Without prompt intervention, this can be fatal. Nonclassic CAH symptoms are subtler and may not emerge until later childhood or adulthood. Females might experience hirsutism (excessive hair growth), severe acne, irregular menstrual cycles, or infertility, sometimes misdiagnosed as polycystic ovary syndrome. Males could have early puberty or fertility issues, though many remain asymptomatic. Across all forms, untreated CAH can lead to complications like obesity, insulin resistance, and bone density loss due to chronic hormone imbalances. Recognizing these signs early is crucial, as they can profoundly impact physical, emotional, and reproductive health.

Diagnostic Approaches and Early Detection

Diagnosis of CAH has advanced significantly, thanks to routine newborn screening programs implemented in many countries, including the United States. This involves a simple heel prick blood test shortly after birth to measure levels of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP), a marker elevated in 21-hydroxylase deficiency. High levels prompt further testing, such as electrolyte panels, hormone assays, and ACTH stimulation tests, which assess the adrenal glands' response to synthetic ACTH. For ambiguous genitalia, imaging like pelvic ultrasound and genetic testing help confirm the diagnosis and determine chromosomal sex.

Prenatal diagnosis is possible for at-risk pregnancies through chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, allowing early intervention if needed. In nonclassic CAH, diagnosis often occurs later when symptoms like early puberty or menstrual irregularities lead to blood tests showing mildly elevated 17-OHP. Genetic testing identifies specific mutations, aiding in family planning and personalized care. Overall, early detection through screening has dramatically reduced mortality from adrenal crises, emphasizing the value of these programs in public health.

Treatment Strategies and Lifelong Management

While there's no cure for CAH, effective treatments focus on hormone replacement to restore balance and prevent complications. For classic CAH, lifelong glucocorticoid therapy, such as hydrocortisone or prednisone, replaces missing cortisol, with doses adjusted during stress to mimic natural production. Mineralocorticoid replacement with fludrocortisone addresses aldosterone deficiency, often paired with salt supplements in infants to prevent salt-wasting crises. Monitoring involves regular blood tests for hormone levels, electrolytes, and growth markers to fine-tune dosages and avoid side effects like weight gain or osteoporosis.

In females with ambiguous genitalia, surgical options may be considered to improve function or appearance, typically between 2 to 6 months of age, though decisions should involve multidisciplinary teams including endocrinologists, surgeons, and psychologists. For nonclassic CAH, treatment is symptom-based; low-dose glucocorticoids may control androgen excess, while oral contraceptives or anti-androgens like spironolactone help with menstrual irregularities or hirsutism. Fertility support, such as ovulation induction, is available for those facing challenges. Psychological support is integral, addressing body image, gender identity, and chronic illness management to enhance quality of life. With adherence, most individuals achieve normal growth, puberty, and fertility.

Potential Complications and Preventive Measures

Untreated or poorly managed CAH can lead to serious complications. Adrenal crises remain a risk in classic forms, necessitating emergency kits with injectable hydrocortisone and education on stress dosing. Long-term androgen excess may cause virilization, infertility, or metabolic issues like insulin resistance. Bone health can suffer from chronic glucocorticoid use, increasing osteoporosis risk, so calcium and vitamin D supplementation, along with DEXA scans, are recommended.

Prevention starts with genetic counseling for carriers, who have a 25 percent chance of having an affected child per pregnancy. Prenatal treatment with dexamethasone can reduce virilization in female fetuses, though it's controversial due to potential side effects. Lifestyle measures, including a balanced diet, exercise, and stress management, complement medical therapy to mitigate risks.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

Recent advancements are transforming CAH management. In 2024, the FDA approved crinecerfont, a new medication that reduces the need for high glucocorticoid doses by targeting corticotropin-releasing factor receptors, potentially minimizing side effects. Gene therapy trials aim to correct underlying mutations, offering hope for a cure. Research into biomarkers for better monitoring and personalized medicine is ongoing, with studies exploring the long-term impacts on fertility and mental health. Clinical trials, accessible via sites like ClinicalTrials.gov, focus on novel therapies and improved newborn screening accuracy.

Living Well with CAH: A Path Forward

In conclusion, Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, though challenging, is manageable with early diagnosis, tailored treatment, and ongoing support. From understanding its genetic roots to embracing modern therapies, individuals with CAH can thrive, contributing to society while maintaining their health. If you suspect CAH or seek more information, consult healthcare professionals for personalized guidance. Advances in research promise even brighter futures, reminding us that knowledge is the key to unlocking better outcomes for all affected by this condition.

ADVERTISEMENT